Encode celebrates key victory following months of advocacy for bipartisan bill to combat online intimate image abuse.

Category: In the News

Newsom vetoes landmark AI safety bill backed by Californians

Full Article: The Guardian

Governor Gavin Newsom of California recently killed SB1047, a first-of-its-kind artificial intelligence safety bill, arguing that its focus on only the largest AI models leaves out smaller ones that can also be risky. Instead, he says, we should pass comprehensive regulations on the technology.

If this doesn’t sound quite right to you, you’re not alone.

Despite claims by prominent opponents of the bill that “literally no one wants this”, SB1047 was popular – really popular. It passed the California legislature with an average of two-thirds of each chamber voting in favor. Six statewide polls that presented pro and con arguments for the bill show strong majorities in support, which rose over time. A September national poll found 80% of Americans thought Newsom should sign the bill. It was also endorsed by the two most-cited AI researchers alive, along with more than 110 current and former staff of the top-five AI companies.

The core of SB1047 would have established liability for creators of AI models in the event they cause a catastrophe and the developer didn’t take appropriate safety measures.

These provisions received support from at least 80% of California voters in an August poll.

So how do we make sense of this divide?

The aforementioned surveys were all commissioned or conducted by SB1047-sympathetic groups, prompting opponents to dismiss them as biased.

But even when a bill-sympathetic polling shop collaborated with an opponent to test “con” arguments in September, 62% of Californians were in favor.

Moreover, these results don’t surprise me at all. I’m writing a book on the economics and politics of AI and have analyzed years of nationwide polling on the topic. The findings are pretty consistent: people worry about risks from AI, favor regulations, and don’t trust companies to police themselves. Incredibly, these findings tend to hold true for both Republicans and Democrats.

So why would Newsom buck the popular bill?

Well, the bill was fiercely resisted by most of the AI industry, including Google, Meta and OpenAI. The US has let the industry self-regulate, and these companies desperately don’t want that to change – whatever sounds their leaders make to the contrary.

AI investors such as the venture fund Andreessen Horowitz, also known as a16z, mounted a smear campaign against the bill, saying anything they thought would kill the bill and hiring lobbyists with close ties to Newsom.

AI “godmother” and Stanford professor Fei-Fei Li parroted Andreessen Horowitz’s misleading talking points about the bill in the pages of Fortune – never disclosing that she runs a billion-dollar AI startup backed by the firm.

Then, eight congressional Democrats from California asked Newsom for a veto in an open letter, which was first published by an Andreessen Horowitz partner.

The top three names on the congressional letter – Zoe Lofgren, Anna Eshoo, and Ro Khanna – have collectively taken more than $4m in political contributions from the industry, accounting for nearly half of their lifetime top-20 contributors. Google was their biggest donor by far, with nearly $1m in total.

The death knell probably came from the former House speaker Nancy Pelosi, who published her own statement against the bill, citing the congressional letter and Li’s Fortune op-ed.

In 2021, reporters discovered that Lofgren’s daughter is a lawyer for Google, which prompted a watchdog to ask Pelosi to negotiate her recusal from antitrust oversight roles.

Who came to Lofgren’s defense? Eshoo and Khanna.

Three years later, Lofgren remains in these roles, which have helped her block efforts to rein in big tech – against the will of even her Silicon Valley constituents.

Pelosi’s 2023 financial disclosure shows that her husband owned between $16m and $80m in stocks and options in Amazon, Google, Microsoft and Nvidia.

When I asked if these investments pose a conflict of interest, Pelosi’s spokesperson replied: “Speaker Pelosi does not own any stocks, and she has no prior knowledge or subsequent involvement in any transactions.”

SB1047’s primary author, California state senator Scott Wiener, is widely expected to run for Pelosi’s congressional seat upon her retirement. His likely opponent? Christine Pelosi, the former speaker’s daughter, fueling speculation that Pelosi may be trying to clear the field.

In Silicon Valley, AI is the hot thing and a perceived ticket to fortune and power. In Congress, AI is something to regulate … later, so as to not upset one of the wealthiest industries in the country.

But the reality on the ground is that AI is more a source of fear and resentment. California’s state legislators, who are more down-to-earth than high-flying national Democrats, appear to be genuinely reflecting – or even moderating – the will of their constituents.

Sunny Gandhi of the youth tech advocacy group Encode, which co-sponsored the bill, told me: “When you tell the average person that tech giants are creating the most powerful tools in human history but resist simple measures to prevent catastrophic harm, their reaction isn’t just disbelief – it’s outrage. This isn’t just a policy disagreement; it’s a moral chasm between Silicon Valley and Main Street.”

Newsom just told us which of these he values more.

Encode founder Sneha Revanur and Grey’s Anatomy star Jason George: Governor Newsom’s Chance to Lead on AI Safety

Twenty years ago, social media was expected to be the great democratizer, making us all more ‘open and connected’ and toppling autocratic governments around the world. Those early optimistic visions simply missed the downside. We watched as it transformed our daily lives, elections, and the mental health of an entire generation. By the time its harms were well-understood, it was too late: the platforms were entrenched and the problems endemic. California Senate Bill 1047 aims to ensure we don’t repeat this same mistake with artificial intelligence.

AI is advancing at breakneck speed. Both of us are strong believers in the power of technology, including AI, to bring great benefits to society. We don’t think that the progress of AI can be stopped, or that it should be. But leading AI researchers warn of imminent dangers—from facilitating the creation of biological weapons to enabling large-scale cyberattacks on critical infrastructure. It’s not a far off future – today’s AI systems are flashing warning signs of dangerous capabilities. OpenAI just released a powerful new system that it rated as “medium” risk for enabling chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear weapons creation–up from the “low” risk posed by its previous system. A handful of AI companies are significantly increasing the risk of major societal harms, without our society’s consent, and without meaningful transparency or accountability. They are asking us to trust them to manage that risk, on our behalf and by themselves.

We have a chance right now to say that the people have a stake and a voice in protecting the public interest. SB 1047, recently passed by the California state legislature, would help us get ahead of the most severe risks posed by advanced AI systems. Governor Gavin Newsom now has until September 30th to sign or veto the bill. With California home to many leading AI companies, his decision will reverberate globally.

SB 1047 has four core provisions: testing, safeguards, accountability, and transparency. The bill would require developers of the most powerful AI models to test for the potential to cause catastrophic harm and implement reasonable safeguards. And it would hold them accountable if they cause harm by failing to take these common sense measures. The bill would also provide vital transparency into AI companies’ safety plans and protect employees who blow the whistle on unsafe practices.

To see how these requirements are common sense, consider car safety. Electric vehicle batteries can sometimes explode, so the first electric vehicles were tested extensively to develop procedures for safely preventing explosions. Without such testing, electric vehicles may have been involved in many disasters on the road – and damaged consumer trust in the technology for years to come. The same is true of AI. The need for safeguards, too, is straightforward. It would be irresponsible for a company to sell a car designed to drive as fast as possible if it lacked basic safety features like seatbelts. Why should we treat AI developers differently?

Governor Newsom has already signed several other AI-related bills this session, such as a pair of bills protecting the digital likeness of performers. While those bills are important, they are not designed to prevent the very serious risks that SB 1047 addresses – risks that affect all of us.

If Governor Newsom signs SB 1047, it won’t be the first time that California has led the country in protecting the public interest. From data privacy to emissions standards, California has consistently moved ahead of the Federal government to protect its residents against major societal threats. This opportunity lies on the Governor’s desk once more.

The irony is, AI developers have already – voluntarily – committed to many of the common sense testing and safeguard protocols required by SB 1047, at summits convened by the White House and in Seoul. But strangely, these companies resist being held accountable if they fail to keep their promises. Some have threatened that they will leave California if the bill is passed. That’s nonsense. As Dario Amodei, the CEO of Anthropic, has said, such talk is just “theater” and “bluster” that “bears no relationship to the actual content of the bill.” The story is depressingly familiar – the tech industry has made such empty threats before to coerce California into sparing it from regulation. It’s the worst kind of deja vu. But California hasn’t caved to such brazen attempts at coercion before, and Governor Newsom shouldn’t cave to them now.

SB 1047 isn’t a panacea for all AI-related risks, but it represents a meaningful, proactive step toward making this technology safe and accountable to our democracy and to the public interest. Governor Newsom has the opportunity to lead the nation in governing the most critical technology of our time. And as this issue only grows in importance, this decision will become increasingly important to his legacy. We urge him to seize this moment and sign SB 1047.

Jason Winston George is an actor best known for his role as Dr. Ben Warren on Grey’s Anatomy and Station 19. A member of the SAG-AFTRA National Board, he helped negotiate the union’s contract on AI provisions.

Sneha Revanur is the Founder and President of Encode Justice.

Our conversation with Joseph-Gordon Levitt, actor and AI 2030 signatory

What Gen Z wants from AI policymakers

Youth call on world leaders to set AI safeguards by 2030

Interview with Sneha Revanur, “the Greta Thunberg of AI”

Every year, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists sets the hands of its iconic Doomsday Clock—a graphic representation of how close the world is to global disaster. And every year, there’s a huge influx of comments from readers despairing “This is awful; what can I do?”

So, one of the things that we did for this issue of the magazine was to look for people who are making an effort—whether on a local, regional, or national scale—to keep the Clock from striking midnight.

The candidates we looked at came from all walks of life, with all sorts of backgrounds and interests, tackling all sorts of different threats. They were old and young—and some of them were quite young indeed. At the age of 15, Sneha Revanur founded an organization, Encode Justice, to deal with the harmful implications of artificial intelligence (AI). Now a college sophomore, she made Time Magazine’s list of 100 most influential people in September and has been described by Politico as the “Greta Thunberg of AI.”

In this interview with Bulletin executive editor Dan Drollette Jr., Revanur describes how she got interested in the problem and what caused her to found a youth-led, AI-focused civil-society group. She tells about how her friends went from thinking “Sneha does this AI thing and just like, skips class and goes to D.C. sometimes” to expressing genuine concern about some of the problems associated with AI—which include rendering their dream jobs obsolete, surveilling them around the clock, and inserting deep fakes that pollute their social media. And all that in addition to outright AI-enhanced catastrophes.

Encode Justice now has 900 young members in 30 countries around the world and has drawn comparisons to earlier youth-led climate and gun-control movements. Revanur and her peers were invited to the White House; participated in efforts to legislate for a better, safer AI future; wrote op-eds for The Hill; and helped to successfully defeat a state ballot initiative that would have inserted biased AI-generated algorithms into the justice process—showing how much just one person can accomplish at the grass-roots level.

(Editor’s note: This interview has been condensed and edited for brevity and clarity.)

Dan Drollette Jr.: Where are you from?

Sneha Revanur: I’m originally from California—San Jose, right in the heart of Silicon Valley.

Drollette: Did that have an influence on your interest in artificial intelligence?

Revanur: I definitely would say so. My older sister works in tech, and both my parents are software engineers. So tech was always right in my face, and it got me to thinking about how to guide it in the right direction. My parents are always making jokes about how I’m out to regulate them.

But seriously, this all meant that I was exposed early on to a culture of thinking that every problem in society can be fixed with some sort of computational solution—whether that’s a mobile app, a machine-learning model, or some other mechanism to respond to something. I think that there was always this view that innovation was some sort of silver bullet.

And I think that view has exploded in recent years, with the rise of AI.

I often say that, had I been born anywhere else, Encode Justice would not exist. I really think that growing up in Silicon Valley, in the kind of household I did, was really, really pivotal in shaping me—and shaping the formation of this organization.

Drollette: How did the organization come to be called “Encode Justice”?

Revanur: I came up with the name. And I gave a lot of thought to its connotations—everything about it was very intentional. I mean, I could have chosen a name for the organization that contained a very negative view of technology.

But what I think is so powerful about the name “Encode Justice” is that it captures the sense that our organization’s goal is not about stopping all technology, nor is it about putting an end to innovation. Instead, we are trying to re-imagine what we do have and build justice into the frameworks of these systems from the very beginning. It actually is a call to action, instead of a call to shut things down or give up.

And I think that is a really powerful approach. Even as we are on the brink of potentially catastrophic threats, I remain grounded in the belief that if we act fast, we can get this right; we just need to move to set some rules of the road. If we do that, then AI still can be a force for good; it can open up realms of possibility.

So, I do believe that the message captured in the name Encode Justice still holds true and has as much meaning all these years later.

Drollette: When was the organization started?

Revanur: In the summer of 2020.

Drollette: So, if you’re in your second year of college right now, then at that time you would have been …

Revanur: Fifteen years old.

Drollette: Can you tell me how it came about?

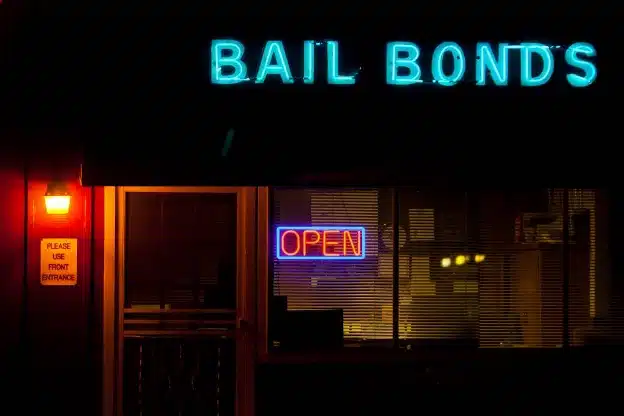

Revanur: It’s an interesting story. A few years ago, I came across an investigation conducted by ProPublica that uncovered pretty staggering rates of racial bias in an algorithm that was being used by justice systems nationwide to evaluate the risk of a given person breaking the law again.[1]

The problem with the algorithm was that it was twice as likely to falsely predict that black defendants relative to white defendants would recidivate—that is, re-offend.

That was a rude awakening for me, because like most people, I tended to view algorithms as perfectly objective, perfectly scientific, and perfectly neutral. It’s difficult for us to conceptualize that these seemingly impenetrable mathematical formulae could actually, you know, purvey injustice or convey some of the worst aspects of human society.

It became clear to me that this was an issue that I would be interested in.

A couple of years later, I came across a ballot measure in my home state of California called “California Proposition 25,” that sought to enshrine the use of very similar algorithms statewide in our legal system. If it passed, it would have replaced the already unjust system of cash bail with an algorithmic tool that was very similar to the tool that had been essentially indicted in this ProPublica investigation, and it would pretty much have been used in all pre-trial cases.

I realized there was very little public awareness about the potential dangers of introducing algorithmic supplements into the process.[2] And there was even less youth participation in the conversation about this technology—and I think youth participation is so critical, because whatever the system is, that’s the system that we’re going to inherit entering adulthood.

So I began to rally my peers.

Together, we contacted voters, created informational content, partnered with community organizations across California, ran phone banks, and were eventually able to defeat the measure by around a 13-percent margin.

Now at that point, we were just a campaign focused on a single ballot measure. But after our initial victory, I realized that we have this incredible network of youth in place, not just from California, but from all over the world—about 900 high school and college students, from 30 different countries—who are fired up and thinking more critically about the implications of AI.

I began thinking that we could take that and really make something.

That’s the point where we became a more formal, full-fledged organization, able to take on other projects—such as facial recognition technology, surveillance and privacy issues, democratic erosion, and all sorts of other risks from AI, from disinformation to labor displacement.

And I think that over the last year, it’s become apparent that there are many new and unanticipated risks of catastrophic harm from AI; for example, ChatGPT 4 has been already “jailbroken” to generate bomb-making instructions.[3] And AI that was intended for drug discovery has already been re-purposed to design tens of thousands of lethal chemical weapons in just hours.[4]

We’re seeing systems slipping out of our control; we are moving towards increasingly powerful, increasingly sophisticated systems that could potentially have grave existential harms for humanity.

Consequently, organizations like Encode Justice are shifting towards making sure we can prepare for those threats, while at the same time not losing sight of the realities that we’re already face-to-face with.

Drollette: Did you have any idea that Encode Justice was going to be this successful? How many folks were a part of it when you started?

Revanur: I think it was really just 20 or 30 kids in the beginning. And a lot of them were from my school or neighboring schools, all in California.

And at that point, it was pretty skewed towards California, because we’d been working on a California issue.

To be quite frank, I honestly never envisioned it would grow as large as it has.

And I think the reason why it’s been so well received is that it is really a product of the times. Over the last year, we’ve seen an absolute explosion of interest—almost hysteria—in AI. Had that not taken place, then there really wouldn’t have been all this attention and visibility around the work that we’re doing. We just jumped into the space at the exact right moment.

It’s pretty astonishing.

Drollette: What’s next for Encode Justice? I believe you folks are working on something called the “Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights”?

Revanur: That’s actually a project that the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy [OSTP] released last year in 2022. My involvement was in advising OSTP on crafting those principles, making sure that they reflected youth priorities.

We actually first came in contact with OSTP in early 2022, when they were first beginning to mull over that project. There was a brief lull when the project fell to the wayside while there were some changes in agency leadership, but over the summer of 2022, we did a lot of advocacy—contacting senators and ensuring that it was moved back to the top of the priority list. We wrote an op-ed in The Hill, in collaboration with Marc Rotenberg of the Center for AI and Digital Policy, calling on the new OSTP director nominee to reprioritize the AI Bill of Rights.

And eventually the framework was released. It definitely is a great starting point—but at the moment, the framework and the principles in the AI Bill of Rights are not enforceable, they’re merely a blueprint. So obviously, there’s a lot of work that has to be done to ensure that we are following up on that critical work by actually passing regulations with real teeth.[5]

I think it really does speak to the urgency of this issue, that Washington is finally summoning up the political will to take meaningful action. And so I really do hope that we can translate some of the very promising ideas and principles in the Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights into actually enforceable regulations.[6]

Drollette: As a journalist, I think I’ve noticed a change in how Big Tech is typically covered in the press. About 10 or so years ago, everything that I ran across in the popular press about computing tended to be along the lines of a fawning “rah, rah, everything is wonderful, tech can never do anything wrong” kind of coverage. Do you get the impression among your peers that there’s more of a realization that tech can bring problems as well as benefits?

Revanur: I think the tides are turning—but to be quite frank, I don’t think we’re there yet. I think that there is still this kind of residual prevailing sense of almost unchecked and unqualified optimism.

To be clear, I share some of that optimism as well, in the sense that I believe that technology has the potential to be a force for the positive transformation of society. I think that there’s so much that technology could do for humanity.

But I think we’ve seen firsthand that problems come up.

So, while I think that the tide is turning, it will take a while yet to complete.

And I think that if the tide is turning, it is turning unevenly. It is taking place in my generation in particular, whereas older generations are more removed from the frontline impacts of technology—and so are less skeptical of it. So yeah, I think it’s slowly but surely trending in the direction of a more qualified rather than unqualified optimism, but not uniformly.

Drollette: So maybe it could be said that technology can be a force for good but needs to be actively steered in that direction—especially by those affected?

Revanur: I think that framing this as a matter of steering is apt, because I think it implies that there is a human duty and a moral responsibility on our part to do that steering. And I think that that will come in the form of really meaningful rules of the road for artificial intelligence, that will come in the form of urgent action to ensure that we are addressing both immediate risks and longer-term, still-unrealized risks from AI. And so it really is going to depend on our swift action.

And I think that we are at a point in time right now, where it very well could be possible that we could lose meaningful human control of AI systems as we know it. And I think that’s why it’s incredibly important that we act fast—because the costs could be unrecoverable otherwise.

Drollette: One of the things that I’ve been hearing is that generally youth these days are kind of apathetic, that they don’t feel that they can really make much of a difference. By that, I mean that youth can see what the problems are, but don’t think they can help contribute to a solution. Is that the kind of thing you’ve observed? Or are you the exception that proves the rule—the anomaly on campus, who’s been down to Washington to push for change?

Revanur: I definitely wouldn’t say that I’m anomalous at all. I think it’s really important to highlight that while I lead this organization, it’s not just as one individual person—there’s a movement of 900 high school and college students around me.

So I think that it would not be right to describe my generation as apathetic when obviously, all the work that I’m doing is supported and fortified by this incredibly large coalition of youth from literally all over the world.

Though I do think that a couple of years ago, we definitely stood at a position of apathy, because I think that people weren’t able to conceptualize the impact that AI was having on their daily lives. I think that in the past, people tended to view artificial intelligence as this entirely abstract technical phenomenon that’s completely detached from our lived reality.

But I think that over the last year, especially, people everywhere, especially youth, have begun to recognize the impacts that AI could have on us—the risk of hallucinations from large language models, the impacts of social media algorithms. I mean, AI is becoming a part of every aspect of our everyday lives: If you apply for a job, there are algorithms that are curating lists of jobs for you and effectively telling you what to apply for. There are algorithms that are screening your resume, once you actually do submit the application. If you stand trial, there are algorithms that are evaluating you as a defendant. There is surveillance everywhere, using facial recognition-enabled surveillance cameras that have the ability to track your whereabouts and your identity.[7] So I really think that people are becoming more and more cognizant of the ubiquity of artificial intelligence.

And with that recognition, I think that more people are becoming anxious about a dystopian future, and that anxiety is translating into concrete political action. It’s no longer an abstract issue that was only discussed by academics and PhDs.

And that’s part of the reason why, I think, youth-led organizations like Encode Justice are picking up steam.

Drollette: And you’re doing all this while still being a full-time college student—you’re juggling this activism while still dealing with classes, exams, internships, and everything else?

Revanur: It’s definitely challenging. Right now, I’m speaking to you by Zoom from the Williams College library, and then I’ve got a problem set that I’ve got to get to immediately after this call. So, you know, there’s a lot to do, and it’s definitely difficult.

But I think that what has helped me get me through it all is the fact that I’m doing this work alongside so many of my peers who are in a very similar position: Every member of Encode Justice is either in high school or college. What that means is that all of us are navigating a very similar set of responsibilities in terms of having a full course load, internships, jobs, family responsibilities, and obligations outside of our schoolwork.

We are taking on this duty because we realize that our collective future depends on it. We are coming at this issue from different walks of life, different backgrounds, different vantage points, because the clock is ticking and our generation needs to act. So, we are taking some time out of our lives to really put our heads together and work on this. And I think that’s really powerful—and really beautiful.

Meet the Greta Thunberg of AI

Parents just don’t understand … the risks of generative artificial intelligence. At least according to a group of Zoomers grappling with this new force that their elders are struggling to regulate.

While young people often bear the brunt of new technologies, and must live with their long-term consequences, no youth movement has emerged around tech regulation that matches the scope or power of youth climate and gun control activism.

That’s starting to change, though, especially as concerns about AI mount.

Earlier today, a consortium of 10 youth organizations sent a letter to congressional leaders and the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy calling on them to include more young people on AI oversight and advisory boards.

The letter, provided first to DFD, was spearheaded by Sneha Revanur, a first-year student at Williams College in Massachusetts and the founder of Encode Justice, an AI-focused civil society group. As a charismatic teenager who is not shy about condemning “a generation of policymakers who are out of touch,” as she put it in an interview, she’s the closest thing the emerging movement to rein in AI has to its own Greta Thunberg. Thunberg began her rise as a global icon of the climate movement in 2018, at the age of 15, with weekly solo protests outside of Sweden’s parliament.

A native of San Jose in the heart of Silicon Valley, Revanur also got her start in tech advocacy as a 15-year-old. In 2020, she volunteered for the successful campaign to defeat California’s Proposition 25, which would have enshrined the replacement of cash bail with a risk-based algorithmic system.

Encode Justice emerged from that ballot campaign with a focus on the use of AI algorithms in surveillance and the criminal justice system. It currently boasts a membership of 600 high school and college students across 30 countries. Revanur said the group’s primary source of funding currently comes from the Omidyar Network, a self-described “social change venture” led by left-leaning eBay founder Pierre Omidyar.

Revanur has become increasingly preoccupied with generative AI as it sends ripples through societies across the world. The aha moment came when she read that February New York Times article about a seductive, conniving AI chatbot. In recent weeks, concerns have only grown about the potential for generative AI to deceive and manipulate people, as well as the broader risks posed by the potential development of artificial general intelligence.

“We were somewhat skeptical about the risks of generative AI,” Revanur says. “We see this open letter as a marking point that we’re pivoting.”

The letter is borne in part out of concerns that older policymakers are ill-prepared to handle this rapidly developing technology. Revanur said that when she meets with congressional offices, she is struck by the lack of tech-specific expertise. “We’re almost always speaking to a judiciary staffer or a commerce staffer.” State legislatures, she said, tend to be worse.

One sign of the generational tension at play: Today’s letter calls on policymakers to “improve technical literacy in government.”

The letter comes at a time when the fragmented youth tech movement is starting to coalesce, according to Zamaan Qureshi, co-chair of Design It For Us Coalition, a signatory of the AI letter.

“The groups that are out there have been working in a disjointed way,” Qureshi, a junior at American University in Washington, said. The coalition grew out of a successful campaign last year in support of the California Age Appropriate Design Code, a state law governing online privacy for children.

To improve coordination on tech safety issues, Qureshi and a group of fellow activists launched the Design It For Us Coalition at the end of March with a kickoff call featuring advisory board member Frances Haugen, the Facebook whistleblower. The coalition is currently focused on social media, which is often blamed for a teen mental health crisis, Qureshi said.

But it’s the urgency of AI that prompted today’s letter.

So, is this the issue that will catapult youth tech activists to the same visibility and influence of other youth movements?

Qureshi said he and his fellow organizers have been in touch with youth climate activists and with organizers from March for Our Lives, the student-led gun control organization.

And the tech activists are looking to push their weight around in 2024.

Revanur, who praised President Joe Biden for prioritizing tech regulation, said Encode Justice plans to make an endorsement in the upcoming presidential race, and is watching to see what his administration does on AI. The group is also considering congressional and state legislative endorsements.

But endorsements and a politely-worded letter are a far cry from the combative — and controversial — tactics that have put the youth climate movement in the spotlight, such as a 2019 confrontation with Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein inside her Bay Area office.

Tech activists remain open to the adversarial approach. Revanur said the risks of AI run amuck could justify “more confrontational” measures going forward.

“We definitely do see ourselves expanding direct action,” she said, “because we have youth on the ground.”

The young activists shaking up the kids’ online safety debate

When lawmakers began investigating the impact of social media on kids in 2021, Zamaan Qureshi was enthralled.

Since middle school he’d watched his friends struggle with eating disorders, anxiety and depression, issues he said were “exacerbated” by platforms like Snapchat and Instagram.

Qureshi’s longtime concerns were thrust into the national spotlight when Meta whistleblower Frances Haugen released documents linking Instagram to teen mental health problems. But as the revelations triggered a wave of bills to expand guardrails for children online, he grew frustrated at who appeared missing from the debate: young people, like himself, who’d experienced the technology from an early age.

“There was little to no conversation about young people and … what they thought should be done,” said Qureshi, 21, a rising senior at American University.

So last year, Qureshi and a coalition of students formed Design It For Us, an advocacy group intended to bring the perspectives of young people to the forefront of the debate about online safety.

They are part of a growing constellation of youth advocacy and activist organizations demanding a say as officials consider new rules to govern kids’ activity online.

The slew of federal and state proposals has served as a rallying cry to a cohort of activists looking to shape laws that may transform how their generation interacts with technology. As policymakers consider substantial shifts to the laws overseeing kids online, including measures at the federal and state level that ban children under 13 from accessing social media and require those younger than 18 to get parental consent to log on, the young advocates — some still in their teens — have been quick to engage.

Now, youth activists have become a formidable lobbying force in capitals across the nation. Youth groups are meeting with top decision-makers, garnering support from the White House and British royalty and affecting legislative proposals, including persuading federal lawmakers to scale back parental control measures in one major bill.

“The tides definitely are turning,” said Sneha Revanur, 18, another member of Design It For Us.

Yet this prominence doesn’t necessarily translate to influence. Many activists said their biggestchallenge is ensuring that policymakers take their input seriously.

“We want to be seen as meaningful collaborators, and not just a token seat at the table,” Qureshi said.

In Washington, D.C., Design It For Us has taken part in dozens of meetings with House and Senate leaders, White House officials and other advocates. In February, the group made its debut testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

“We cannot wait another year, we cannot wait another month, another week or another day to begin to protect the next generation,” Emma Lembke, 20, who co-founded the organization with Qureshi, said in her testimony.

Sen. Richard J. Durbin (D-Ill.), who chairs the panel and met with the group again in July, said that Lembke “provided powerful testimony” and that their meetings were one of “many conversations that I’ve had with young folks demonstrating the next generation’s call for change.”

Revanur said policymakers often put too much stock in technical or political expertise and not enough in digital natives’ lifetime of experience and understanding of technology’s potential for harm.

“There’s so much emphasis on a specific set of credentials: having a PhD in computer science or having spent years working on the Hill,” said Revanur, a rising sophomore at Williams College. “It diminishes the importance of the credentials that youth have, which is the credential of lived experience.”

Revanur, who founded the youth-led group Encode Justice, which focuses on artificial intelligence, has met with officials at the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), urging them to factor in concerns about how AI could be used for school surveillance as they drafted a voluntary AI bill of rights.

The office’s former acting director, Alondra Nelson, who led the initiative, said Encode Justice brought policy issues “to life” by describing both real and imagined harms — from “facial recognition cameras in their school hallways [to] the very real anxiety that the prospect of persistent surveillance caused them.”

In July, Vice President Harris invited Revanur to speak at a roundtable on AI with civil rights and advocacy group leaders, a moment the youth activist called “a pretty significant turning point” in “increasing legitimization of youth voices in the space.”

An honor to join @VP (alongside @WHOSTP & @neeratanden) for an AI roundtable with civil society leaders. Never before has a young person had a voice in federal AI policy!

— Sneha Revanur (@sneharevanur) July 18, 2023

We discussed ChatGPT in the classroom, algorithms & youth mental health, risks from advanced AI, & more. pic.twitter.com/MI0KeONOHG

There are already signs that those in power are heeding their calls.

Sam Hiner, 20, started college during the covid-19 pandemic and said that social media hurt his productivity and ability to socialize on campus.

“It’s easier to scroll on your phone in your dorm than it is to go out because you get that guaranteed dopamine,” said Hiner, a student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Hiner, who in high school co-founded a youth-oriented policy group, worked with lawmakers and children’s safety groups to introduce state legislation prohibiting platforms from using minors’ data to algorithmically target them with content.

He said he held more than 100 meetings with state legislators, advocates and industry leaders as he pushed for a bill to tackle the issue. The state bill, the Social Media Algorithmic Control in Information Technology Act, now has more than 60 sponsors.

Last month, Prince Harry and Meghan, Duchess of Sussex, awarded Hiner’s group, Design It For Us and others grants ranging from $25,000 to $200,000 for their advocacy as part of the newly launched Responsible Technology Youth Power Fund. Hiner said he received a surprise call from the royals minutes after learning about the grant.

“As a young person who … has a bit of a chip on my shoulder from feeling excluded from the process traditionally, getting that … buy-in from some of the most influential people in the world was really cool,” he said.

Youth activists’ lobbying efforts are also bearing fruit in Washington.

This summer, Design It For Us led a week of action calling on senators to take up a bill to expand existing federal privacy protections for younger users, the Children and Teens’ Online Privacy Protection Act, and another measure to create a legal obligation for tech platforms to prevent harms to kids, the Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA).

Great to meet young activists with @DesignItForUs this afternoon.@JudiciaryDems are on a mission to protect kids online. These youth advocates have experienced the ills of social media firsthand.

— Senator Dick Durbin (@SenatorDurbin) July 18, 2023

I’m grateful for their efforts, turning their experience into change. pic.twitter.com/zfG2F4YN6P

A Senate Democratic aide, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the negotiations, said the advocates played a key role in persuading lawmakers to exclude teens from a provision in KOSA requiring parental consent to access digital platforms. It now only covers those 12 and younger.

Dozens of digital rights groups have expressed concern that the legislation would require tech companies to collect even more data from kids and give parents too much control over their children’s online activity, which could disproportionately harm young LGBT users.

“We were focused on making sure that KOSA did not turn into a parental surveillance bill,” said Qureshi.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.), the lead sponsor of the bill, said their mobilization “significantly changed my perspective,” calling their advocacy a “linchpin” to building support for the legislation.

Qureshi and other youth advocates attended a White House event in July at which President Biden surprised spectators by endorsing KOSA and the children’s privacy bill, his most direct remarks on the efforts to date. Days later, the bills advanced with bipartisan support out of the Senate Commerce Committee.

Hiner and other youth advocates said they have worked closely with prominent children’s online safety groups, including Fairplay. Revanur said her group Encode Justice receives funding from the Omidyar Network, an organizationestablished by eBay founder Pierre Omidyar that is a major force in fueling Big Tech antagonists in Washington. Qureshi declined to disclose any funding sources for Design It For Us, beyond its recent grant from the Responsible Technology Youth Power Fund.

Some young activists argue against such tough protections for kids online. The digital activist group Fight for the Future said it has been working with hundreds of young grass-roots activists who are rallying support against the bills, arguing that they would expand surveillance and hurt marginalized groups.

Sarah Philips, 25, an organizer for Fight for the Future, said young people’s views on the topic shouldn’t be treated as a “monolith,” and that the group has heard from an “onslaught” of younger users concerned that policymakers’ proposed restrictions could have a chilling effect on speech online.

“The youth that I work with tend to be queer, a lot of them are trans and a lot of them are young people of color, and their experience in all aspects of the world, including online, is different,” she said.

There are also lingering questions about the science underlying the children’s safety legislation.

Studies have documented that prolonged social media use can lead to increased anxiety and depression and that it can exacerbate body image and self-esteem issues among younger users. But the research on social media use is still evolving. Recent reports by the American Psychological Association and the U.S. Surgeon General painted a more complex picture of the dynamic and called for more research, finding that social media can also generate positive social experiences for young people.

“We don’t want to get rid of social media. That’s not a stance that most members of Gen Z, I think, would take,” said Qureshi. “We want to see reforms and policies in place that make our online world safer and allow us to foster those connections that have been positive.”

Sneha Revanur, the youngest of TIME’s top 100 in AI

Earlier this year, Sneha Revanur began to notice a new trend among her friends: “In the same way that Google has become a commonly accepted verb, ChatGPT just entered our daily vocabulary.” A freshman in college at the time, she noticed that—whether drafting an email to a professor or penning a breakup text—her peers seemed to be using the chatbot for just about everything.

That Gen Z (typically defined as those born between 1997 and 2012) was so quick to adopt generative AI tools was no surprise to Revanur, who at 18 is of a generation that’s been immersed in technology “since day one.” It only makes sense that they also have a say in regulating it.

Revanur’s interest in AI regulation began in 2020, when she founded Encode Justice, a youth-led, AI-focused civil-society group, to mobilize younger generations in her home state of California against Proposition 25, a ballot measure that aimed to replace cash bail with a risk-based algorithm. After the initiative was defeated, the group kept on, focusing on educating and mobilizing peers around AI policy advocacy. The movement now counts 800 young members in 30 countries around the world, and has drawn comparisons to the youth-led climate and gun-control movements that preceded it.

“It’s our generation that’s going to inherit the impacts of the technology that [developers] are hurtling to build at breakneck speed today,” she says, calling the federal government’s inertia on reining in social media giants a warning sign on AI. “It took decades for [lawmakers] to actually begin to take action and seriously consider regulating social media, even after the impacts on youth and on all of our communities had been well documented by that point in time.”

At the urging of many in the AI industry, Washington appears to be moving fast this time. This summer, Revanur helped organize an open letter urging congressional leaders and the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy to include more young people on AI oversight and advisory boards. Soon after, she was invited to attend a roundtable discussion on AI hosted by Vice President Kamala Harris. “For the first time, young people were being treated as the critical stakeholders that we are when it comes to regulating AI and really understanding its impacts on society,” Revanur says. “We are the next generation of users, consumers, advocates, and developers, and we deserve a seat at the table.”